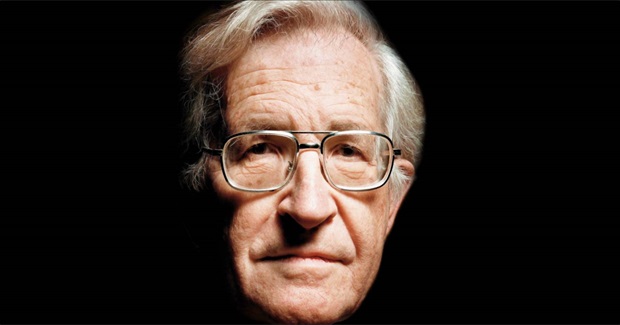

Noam Chomsky Has

'Never Seen Anything Like This'

นอม ชอมสกี้ “ไม่เคยเห็นอะไรเหมือนเอย่างนี้มาก่อน”

By Chris Hedges / truthdig.com

Noam Chomsky is

America’s greatest intellectual. His massive body of work, which includes

nearly 100 books, has for decades deflated and exposed the lies of the power

elite and the myths they perpetrate. Chomsky has done this despite being

blacklisted by the commercial media, turned into a pariah by the academy and,

by his own admission, being a pedantic and at times slightly boring speaker. He

combines moral autonomy with rigorous scholarship, a remarkable grasp of detail

and a searing intellect. He curtly dismisses our two-party system as a mirage

orchestrated by the corporate state, excoriates the liberal intelligentsia for

being fops and courtiers and describes the drivel of the commercial media as a

form of “brainwashing.”

นอม ชอมสกี้

เป็นปัญญาชนที่ยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุดของอเมริกา. งานเขียนพะเรอเกวียนของเขา,

รวมหนังสือเกือบ ๑๐๐ เล่ม, ได้ช่วยปล่อยลมและตีแผ่มุสาของพวกชนชั้นบนที่กุมอำนาจ

และ เทพนิยายที่พวกเขาหล่อเลี้ยงให้คงอยู่.

ชอมสกี้ ได้ทำเช่นนี้ แม้ว่าเขาจะถูกขึ้นบัญชีดำโดยสื่อพาณิชย์,

ได้กลายเป็นคนนอกคอก ในวงนักวิชาการ และ, เขาก็ยอมรับเองว่า, ตนเป็นคนวางภูมิ และ

บางครั้ง ก็เป็นนักพูดที่น่าเบื่อหน่อย.

เขารวมความเป็นตัวของตัวเองเชิงศีลธรรม

กับความเป็นบัณฑิตคงแก่เรียนอย่างเข้มงวด,

เป็นคนที่มีความสามารถพิเศษยิ่งในการเจาะลึกเข้าถึงรายละเอียดของปัญญา. เขาปัดทิ้งระบบสองพรรคของเราอย่างห้วนๆ ว่า

เป็นเพียงเงาลวงตา ที่ปรุงแต่งขึ้นโดยรัฐ-บรรษัท, ตำหนิปัญญาชนเสรีนิยมว่าเป็นพวกขี้โอ่,

มหาดเล็ก/ขี้ประจบ และ บรรยายสิ่งที่พรั่งพรูออกมาจากสื่อพาณิชย์ ว่าเป็นเครื่องมือแบบหนึ่งของการ

“ล้างสมอง”.

And as our nation’s

most prescient critic of unregulated capitalism, globalization and the poison

of empire, he enters his 81st year warning us that we have little time left to

save our anemic democracy.

ในฐานะที่เป็นนักวิพากษ์ต่อทุนนิยมที่ไร้การควบคุม,

โลกาภิวัตน์ และยาพิษแห่งจักวรรรดิ์ ที่โดดเด่นที่สุดในประเทศของเรา, เขาย่างเข้าปีที่

๘๑ เตือนพวกเราว่า เขามีเวลาเหลือน้อยมากที่จะปกป้องประชาธิปไตยโลหิตจางของเรา.

“It is very similar to

late Weimar Germany,” Chomsky told me when I called him at his office in

Cambridge, Mass. “The parallels are striking. There was also tremendous

disillusionment with the parliamentary system. The most striking fact about

Weimar was not that the Nazis managed to destroy the Social Democrats and the

Communists but that the traditional parties, the Conservative and Liberal

parties, were hated and disappeared. It left a vacuum which the Nazis very

cleverly and intelligently managed to take over.”

“มันเหมือนกับเยอรมันยุคไวร์มาร์ในอดีต”,

ชอมสกี้บอกผมเมื่อผมเข้าไปพบที่สำนักงานของเขาที่ แคมบริดจ์. “เปรียบเทียบกันแล้วละม้ายกันมาก. มีการถอดใจ

เหนื่อยหน่ายอย่างยิ่งต่อระบบรัฐสภา. ความจริงที่เด่นชัดมากที่สุดเกี่ยวกับไวร์มาร์

ไม่ใช่อยู่ที่ว่า นาซีจัดการทำลาย พรรคสังคมประชาธิปไตย และ พรรคคอมมิวนิสต์ ได้เอง แต่เป็นเพราะพรรคดั้งเดิม คือ พรรคอนุรักษ์

และพรรคเสรี ถูกเกลียดชังมากและได้หดหายไปเอง.

ทิ้งไว้เป็นสุญญากาศซึ่ง นาซี จัดการยึดครองได้อย่างชาญฉลาด.”

“The United States is

extremely lucky that no honest, charismatic figure has arisen,” Chomsky went

on. “Every charismatic figure is such an obvious crook that he destroys

himself, like McCarthy or Nixon or the evangelist preachers. If somebody comes

along who is charismatic and honest this country is in real trouble because of the

frustration, disillusionment, the justified anger and the absence of any

coherent response. What are people supposed to think if someone says ‘I have

got an answer, we have an enemy’?

“สหรัฐฯ

โชคดียิ่งยวดที่ไม่มีคนที่ซื่อสัตย์, มีบารมีผุดขึ้นมา” ชอมสกี้กล่าว. “ผู้มีบารมีแต่ละคน ล้วนเป็นคนคดในข้องอในกระดูกที่เห็นได้ชัดที่ทำลายตัวเอง,

เช่น แมคคาร์ธี หรือ นิกสัน หรือ พวกนักเทศน์อีแวนเจลิส. หากเกิดมีใครสักคนโผล่ขึ้นมา, เป็นคนที่มีบารมีและซื่อสัตย์,

ในประเทศนี้, เกิดตกลำบาก เพราะเกิดความอึดอัด, ผิดหวัง, โกรธเกรี้ยวอย่างมีเหตุผล

และความที่ไม่มีการตอบสนองที่เป็นเรื่องเป็นราวมีสาระ. แล้วคนทั่วไปควรคิดอย่างไร หากบางคนพูดว่า “ผมมีคำตอบ,

เรามีศัตรู”?

There it was the Jews.

Here it will be the illegal immigrants and the blacks. We will be told that

white males are a persecuted minority. We will be told we have to defend

ourselves and the honor of the nation. Military force will be exalted. People

will be beaten up. This could become an overwhelming force. And if it happens

it will be more dangerous than Germany. The United States is the world power.

ที่โน่น คือ

ชาวยิว. ที่นี่

จะเป็นคนอพยพย้ายถิ่นเข้ามาและคนผิวดำ.

เราจะถูกกรอกหูว่า เพศชายผิวขาว

เป็นชนกลุ่มน้อยที่ถูกประหัตประหารกลั่นแกล้ง.

ว่า เราต้องปกป้องตัวเราเองและเกียรติภูมิของประเทศเรา. กองทัพจะต้องอยู่สูงส่ง. ประชาชนจะต้องถูกทุบตี. นี่จะกลายเป็นกระแสที่ล้นหลาม. และหากมันเกิดขึ้น

มันจะเป็นอันตรายมากกว่าเยอรมัน. สหรัฐฯ

เป็นเจ้าโลก.

Germany was powerful

but had more powerful antagonists. I don’t think all this is very far away. If

the polls are accurate it is not the Republicans but the right-wing Republicans,

the crazed Republicans, who will sweep the next election.”

เยอรมันก็ทรงอำนาจ

แต่มีคู่ปรับที่ทรงพลังกว่า.

ผมไม่คิดว่าสิ่งเหล่านี้ อยู่ไกลออกไปเท่าไร. หากโพลแม่นยำ จะไม่ใช่พรรครีพับลิกัน

แต่เป็นฝักใฝ่ขวาของพรรครีพับลิกัน, พวกรีพับลิกันที่คลั่งไคล้,ที่จะชนะการเลือกตั้งครั้งหน้า”.

“I have never seen

anything like this in my lifetime,” Chomsky added. “I am old enough to remember

the 1930s. My whole family was unemployed. There were far more desperate

conditions than today. But it was hopeful. People had hope. The CIO was

organizing. No one wants to say it anymore but the Communist Party was the

spearhead for labor and civil rights organizing. Even things like giving my

unemployed seamstress aunt a week in the country. It was a life. There is

nothing like that now. The mood of the country is frightening. The level of

anger, frustration and hatred of institutions is not organized in a

constructive way. It is going off into self-destructive fantasies.”

“ผมไม่เคยเห็นอะไรอย่างนี้มาก่อนในชีวิต”

ชอมสกี้พูดต่อ. “ผมอายุมากพอที่จะจำเหตุการณ์ในทศวรรษ

๒๔๗๐. ทั้งครอบครัวของผมตกงาน. สภาวะตอนนั้นยากลำบากกว่าทุกวันนี้. แต่ก็ยังมีความหวัง. คนยุคนั้นมีความหวัง. CIO /สหภาพ? มีระบบระเบียบ/ความเป็นองค์กร. ไม่มีใครต้องการพูดถึงมันอีก

แต่พรรคคอมมิวนิสต์ยุคนั้น เป็นหัวหอกของการจัดกระบวนแรงงานและสิทธิพลเมือง. แม้แต่เรื่องเช่น ให้น้าสาวที่เป็นช่างเย็บผ้าตกงานให้ทำงานในประเทศหนึ่งสัปดาห์. มันเป็นการให้ชีวิต. ตอนนี้ ไม่มีอะไรแบบนั้นแล้ว. อารมณ์ของประเทศ น่ากลัวมาก. ระดับความโกรธเกรี้ยว, ความอึดอัดหุนหัน และ

ความเกลียดของสถาบันต่างๆ ไม่ได้ถูกจัดกระบวนในทางสร้างสรรค์เลย. มันกำลังเถลไถลออกนอกลู่นอกทาง เป็นฝันเฟื่องที่ทำลายตัวเอง”.

“I listen to talk radio,”

Chomsky said. “I don’t want to hear Rush Limbaugh. I want to hear the people

calling in. They are like [suicide pilot] Joe Stack. What is happening to me? I have done all the right

things. I am a God-fearing Christian. I work hard for my family. I have a gun.

I believe in the values of the country and my life is collapsing.”

“ผมนั่งฟังวิทยุ. ผมไม่ต้องการจะฟัง Rush Limbaugh

แต่ต้องการฟังคนที่โทรเข้ามา.

พวกเขาเป็นเหมือน (นักบินฆ่าตัวตาย) Joe Stack. เกิดอะไรขึ้นกับผม? ผมได้ทำทุกอย่างที่ถูกต้อง.

ผมเป็นคริสเตียนที่เกรงกลัวพระเจ้า. ผมทำงานหนักเพื่อครอบครัวของผม. ผมมีปืน.

ผมเชื่อในค่านิยมของประเทศ และ ชีวิตของผมกำลังพังทลายลง”.

Chomsky has, more than

any other American intellectual, charted the downward spiral of the American

political and economic system, in works such as “On Power and Ideology: The

Managua Lectures,” “Rethinking Camelot: JFK, the Vietnam War, and US Political

Culture,” “A New Generation Draws the Line: Kosovo, East Timor and the

Standards of the West,” “Understanding Power: The Indispensable Chomsky,”

“Manufacturing Consent” and “Letters From Lexington: Reflections on

Propaganda.” He reminds us that genuine intellectual inquiry is always

subversive. It challenges cultural and political assumptions. It critiques

structures. It is relentlessly self-critical. It implodes the self-indulgent

myths and stereotypes we use to elevate ourselves and ignore our complicity in

acts of violence and oppression. And it makes the powerful, as well as their

liberal apologists, deeply uncomfortable.

ชอมสกี้ ได้ทำมากกว่าปัญญาชนอเมริกันคนอื่นๆ

ในการวาดผังแสดงการดิ่งพสุธาของระบบการเมืองและเศรษฐกิจอเมริกัน, ในผลงาน เช่น “อำนาจและอุดมการณ์: ปาฐกถา มานากัว”, “คิดใหม่เรื่องอัศวินโต๊ะกลม: JFK/เคนาดี้, สงครามเวียดนาม, และวัฒนธรรมการเมืองสหรัฐฯ”, “คนรุ่นใหม่ขีดเส้นแบ่ง:

โคโซโว, ติมอร์ตะวันออก และ มาตรฐานตะวันตก”, “ทำความเข้าใจกับอำนาจ: ชอมสกี้ ผู้ขาดเสียไม่ได้”, “การผลิตเอกฉันท์” และ “จดหมายจากเล็กซิงตัน: สะท้อนโฆษณาชวนเชื่อ”. เขาเตือนว่า

การสืบสวนของปัญญาชน เป็นไปในทางลักษณะพลิกและคว่ำเสมอ. มันท้าทายสมมติฐานของวัฒนธรรมและการเมือง. มันวิพากษ์โครงสร้าง. มันวิพากษ์ตัวเองอย่างไม่ผ่อนปรน. มันทุบทำลาย เทพนิยายปรนเปรอตัวเอง และภาพเหมารวมที่เรามักใช้เพื่อเชิดชูตัวเราเอง

และเมินเฉยต่อการสมรู้ร่วมคิดในการกระทำรุนแรงและกดขี่. และมันก็ทำให้ผู้มีอำนาจ,

รวมทั้งพวกนักขอโทษขอโพยเสรีนิยม, รู้สึกไม่สบายใจอย่างยิ่ง.

Chomsky reserves his

fiercest venom for the liberal elite in the press, the universities and the

political system who serve as a smoke screen for the cruelty of unchecked

capitalism and imperial war. He exposes their moral and intellectual posturing

as a fraud. And this is why Chomsky is hated, and perhaps feared, more among

liberal elites than among the right wing he also excoriates. When Christopher

Hitchens decided to become a windup doll for the Bush administration after the

attacks of 9/11, one of the first things he did was write a vicious article

attacking Chomsky. Hitchens, unlike most of those he served, knew which

intellectual in America mattered. [Editor’s note: To see some of the

articles in the 2001 exchanges between Hitchens and Chomsky, click here, here, here and here.]

ชอมสกี้

เก็บอสรพิษที่ดุเดือดที่สุดสำหรับชนชั้นบน-เสรีนิยมในวงการสื่อ, มหาวิทยาลัย และ

ระบบการเมือง ผู้ทำหน้าที่เสมือนม่านควันบดบังความโหดเหี้ยมของทุนนิยมที่ไร้การควบคุม

และ สงครามจักรวรรดิ์. เขาเปิดโปงการวางมาดผู้ทรงศีลธรรมและทรงภูมิปัญญาว่าเป็นการสร้างภาพ. เพราะเหตุนี้ เขาจึงเป็นที่เกลียดชัง, และบางทีก็หวาดกลัว,

จะเป็นมากในหมู่ชนชั้นบนเสรีนิยม กว่าพวกเอียงขวาซึ่งได้ถูกเขาสวดไล่เช่นกัน. เมื่อ คริสโตเฟอร์ ฮิตเชนส์ ตัดสินใจเล่นบทเป็นตุ๊กตาไขลานให้รัฐบาลบุ๊ช

หลังจากการบุกรุก 9/11,

หนึ่งในสิ่งแรกที่เขาทำ คือ เขียนบทความอุบาทว์โจมตีชอมสกี้. ฮิตเชนส์, ไม่เหมือนคนส่วนใหญ่ที่เขารับใช้, รู้ว่า

ปัญญาชนคนไหนในอเมริกามีคนเชื่อถือ.

“I don’t bother

writing about Fox News,” Chomsky said. “It is too easy. What I talk about are

the liberal intellectuals, the ones who portray themselves and perceive

themselves as challenging power, as courageous, as standing up for truth and

justice. They are basically the guardians of the faith. They set the limits.

They tell us how far we can go. They say, ‘Look how courageous I am.’ But do

not go one millimeter beyond that. At least for the educated sectors, they are

the most dangerous in supporting power.”

ผมไม่เสียเวลาเขียนเกี่ยวกับข่าวฟอกซ์หรอก...มันง่ายเกินไป. สิ่งที่ผมพูดถึงเป็นปัญญาชนเสรีนิยม, พวกที่อวดตัวเองและมองตัวเองว่ากำลังท้าทายอำนาจ,

ว่าเป็นคนกล้าหาญ, ว่ากำลังลุกขึ้นหาญสู้เพื่อความจริงและความยุติธรรม. แท้จริง พวกเขาเป็นผู้พิทักษ์ความศรัทธา. พวกเขากำหนดขอบเขตจำกัด. พวกเขาบอกพวกเราว่า จะไปได้ไกลถึงแค่ไหน. บอกว่า “ดูซิ ผมกล้าหาญแค่ไหน”. แต่ก็ไม่เดินหน้าไปเกินกว่านั้นแม้แต่มิลลิเมตร. อย่างน้อยสำหรับภาคส่วนผู้มีการศึกษา, พวกเขาเป็นคนที่อันตรายที่สุดในการสนับสนุนอำนาจ”.

Chomsky, because he

steps outside of every group and eschews all ideologies, has been crucial to

American discourse for decades, from his work on the Vietnam War to his

criticisms of the Obama administration. He stubbornly maintains his position as

an iconoclast, one who distrusts power in any form.

ชอมสกี้,

เพราะเหตุที่ได้ก้าวออกนอกเขตของทุกๆ กลุ่ม และ หลีกเลี่ยงอุดมการณ์ทั้งหมด,

ได้เป็นส่วนสำคัญยิ่งของวาทกรรมอเมริกันมาหลายทศวรรษ, จากผลงานของเขาเรื่อง

สงครามเวียดนาม จนถึง คำวิพากษ์ของเขาต่อรัฐบาลโอบามา. เขารักษาจุดยืนของเขาอย่างคนหัวรั้น

ในฐานะเป็นผู้ทำลายลัทธิความเชื่อแบบฝังหัวของประชาชน,

คนที่ไม่ยอมเชื่อถือในอำนาจไม่ว่าจะอยู่ในรูปแบบใด.

“Most intellectuals

have a self-understanding of themselves as the conscience of humanity,” said

the Middle East scholar Norman Finkelstein. “They revel in and admire someone like

Vaclav Havel. Chomsky is contemptuous of Havel. Chomsky embraces theJulien Benda view

of the world. There are two sets of principles. They are the principles of

power and privilege and the principles of truth and justice. If you pursue

truth and justice it will always mean a diminution of power and privilege. If

you pursue power and privilege it will always be at the expense of truth and

justice. Benda says that the credo of any true intellectual has to be, as

Christ said, ‘my kingdom is not of this world.’ Chomsky exposes the pretenses

of those who claim to be the bearers of truth and justice. He shows that in

fact these intellectuals are the bearers of power and privilege and all the

evil that attends it.”

“ปัญญาชนส่วนใหญ่มีความเข้าใจตัวเองว่า

เป็นความสำนึกของมนุษยชาติ” ผู้คงแก่เรียนด้านตะวันออกกลาง นอร์แมน

ฟินเกลสไตน์. “พวกเขาชอบคลุกคลีและเลื่อมใสคนเช่น

Vaclav Havel. ชอมสกี้ ดูถูก Havel แต่ยอมรับมุมมองของ จูเลียน เบนดา ต่อโลก. ซึ่งมีหลักการ ๒ ชุด นั่นคือ

หลักการของ อำนาจและอภิสิทธิ์ และ

หลักการของความจริงและความยุติธรรม.

หากคุณแสวงหาความจริงและความยุติธรรม ย่อมหมายความว่า ต้องสละความจริงและความยุติธรรม. เบนดา กล่าวว่า

ความน่าเชื่อถือของปัญญาชนที่จริงจัง จะต้องเป็นอย่างที่พระคริสต์ตรัส, “ราชอาณาจักรของข้า

ไม่ใช่โลกนี้”. ชอมสกี้

เปิดโปงความเสแสร้งของพวกที่อ้างตัวว่าเป็นผู้ธำรงความจริงและความยุติธรรม. เขาแสดงให้เห็นว่า ปัญญาชนเหล่านี้

เป็นผู้ธำรงอำนาจและอภิสิทธิ์ และ ความชั่วร้ายทั้งมวลที่เกี่ยวข้องกับมัน.”

“Some of Chomsky’s

books will consist of things like analyzing the misrepresentations of the Arias

plan in Central America, and he will devote 200 pages to it,” Finkelstein said.

“And two years later, who will have heard of Oscar Arias? It causes you to

wonder would Chomsky have been wiser to write things on a grander scale, things

with a more enduring quality so that you read them forty or sixty years later.

This is what Russell did in books like‘Marriage and Morals.’ Can

you even read any longer what Chomsky wrote on Vietnam and Central America? The

answer has to often be no. This tells you something about him. He is not

writing for ego. If he were writing for ego he would have written in a grand

style that would have buttressed his legacy. He is writing because he wants to

effect political change. He cares about the lives of people and there the

details count. He is trying to refute the daily lies spewed out by the

establishment media. He could have devoted his time to writing philosophical

treatises that would have endured like Kant or Russell. But he invested in the

tiny details which make a difference to win a political battle.”

“หนังสือบางเล่มของชอมสกี้

จะประกอบด้วยเรื่อง เช่น การวิเคราะห์ การนำเสนอผิดๆ ในแผน Arias ในอเมริกากลาง, และเขาจะอุทิศ

๒๐๐ หน้าเขียนเรื่องนี้” ฟินเกลสไตน์ บอก.

“และหลังจากนั้น ๒ ปี, ใครจะเคยได้ยินชื่อ Oscar Arias? คุณก็จะสงสัยว่า

ชอมสกี้น่าจะเขียนให้ใหญ่หลวงกว่านี้, มีคุณภาพที่ยืนยงกว่านี้ เพื่อว่า

คุณจะได้อ่านในอีก ๔๐ หรือ ๖๐ ปีข้างหน้า.

นี่คือ สิ่งที่ชอมสกี้ได้ทำในหนังสือ เช่น ‘Marriage and

Morals.’ คุณเคยอ่านอะไรที่ยาวกว่างานของชอมสกี้

เรื่องเวียดนาม และ อเมริกากลาง?

คำตอบมักเป็น ไม่.

นี่บอกอะไรเกี่ยวกับเขา.

เขาไม่ได้เขียนสนองอัตตาตัวเอง.

หากเขาเขียนสนองอัตตาตัวเอง เขาคงเขียนด้วยลีลาอลังการ์

ซึ่งจะฉาบตำนานของเขา.

เขาเขียนเพราะต้องการกระแทกให้เกิดการเปลี่ยนแปลงทางการเมือง. เขาแคร์ต่อชีวิตของประชาชน

และนั่นคือสิ่งที่เขาให้รายละเอียด. เขาพยายามเถียงกับการโกหกประจำวัน

ที่สำลักออกมาจากสื่อกระแสหลัก.

เขาสามารถอุทิศเวลาของเขาเขียนตำราปรัชญา ที่จะอยู่ยงคงกะพัน เช่น คานท์

และ รัสเซลล์. แต่เขากลับลงทุนในรายละเอียดยิบย่อยที่สร้างความแตกต่างเพื่อเอาชนะในสงครามการเมือง”.

“I try to encourage

people to think for themselves, to question standard assumptions,” Chomsky said

when asked about his goals. “Don’t take assumptions for granted. Begin by

taking a skeptical attitude toward anything that is conventional wisdom. Make

it justify itself. It usually can’t. Be willing to ask questions about what is

taken for granted. Try to think things through for yourself. There is plenty of

information. You have got to learn how to judge, evaluate and compare it with

other things. You have to take some things on trust or you can’t survive.

“ผมพยายามชักจูงประชาชนให้คิดด้วย/เพื่อตัวเอง,

ให้ตั้งคำถามต่อสมมติฐานมาตรฐาน” ชอมสกี้ กล่าวเมื่อถูกถามถึงเป้าหมายของเขา. “อย่าเชื่อตามสมมติฐานทั้งดุ้นง่ายๆ. ตั้งข้อสงสัยไว้ก่อนต่อทุกอย่างที่เป็น

ภูมิปัญญาที่ถือปฏิบัติกันมา.

ทำให้มันพิสูจน์/ยืนอยู่ด้วยตัวเองได้.

ปกติมันมักจะยืนอยู่เองไม่ได้.

จงยินดีที่จะตั้งคำถาม ว่าอะไรได้ถูกถือเบา. พยายามคิดเรื่องต่างๆ ให้ทะลุแจ่มแจ้งด้วยตัวของคุณเอง. มีข้อมูลมากมาย. คุณต้องเรียนรู้ว่าจะตัดสินอย่างไร, ประเมิน

และ เปรียบเทียบ กับเรื่องอื่นๆ.

คุณต้องรับบางสิ่งที่คุณเชื่อถือได้ ไม่งั้นคุณไปไม่รอด.

But if there is something

significant and important don’t take it on trust. As soon as you read anything

that is anonymous you should immediately distrust it. If you read in the

newspapers that Iran is defying the international community, ask who is the

international community? India is opposed to sanctions. China is opposed to

sanctions. Brazil is opposed to sanctions. The Non-Aligned Movement is

vigorously opposed to sanctions and has been for years. Who is the

international community? It is Washington and anyone who happens to agree with

it. You can figure that out, but you have to do work. It is the same on issue

after issue.”

แต่ถ้ามีบางเรื่องที่มีนัยสำคัญและมีความสำคัญ

อย่ารับมันเพราะความเชื่อถือ. ทันทีที่คุณอ่านบางเรื่องที่นิรนาม

คุณควรเห็นได้ว่าไม่น่าเชื่อถือทันที. หากคุณอ่านในหนังสือพิมพ์ว่า

อิหร่านกำลังยั่วยุประชาคมสากล, จงถามว่า ใครอยู่ในประชาคมสากล? อินเดีย จีน บราซิล คัดค้านการลงโทษ. Non-Aligned Movement คัดค้านการลงโทษอย่างแรง

มาหลายปีแล้ว. ใครเป็นประชาคมสากล? วอชิงตัน และ

ใครก็ตามที่เกิดเห็นด้วยกับมัน. คุณคิดค้นเอาเองได้,

แต่คุณต้องทำงานเอง. มันเป็นประเด็นเดียวกันซ้ำๆ.”

Chomsky’s courage to

speak on behalf of those, such as the Palestinians, whose suffering is often

minimized or ignored in mass culture, holds up the possibility of the moral

life. And, perhaps even more than his scholarship, his example of intellectual

and moral independence sustains all who defy the cant of the crowd to speak the

truth.

ความกล้าหาญของชอมสกี้ในการพูดในนามของผู้อื่น

เช่น ชาวปาเลสไตน์ ซึ่งสื่อกระแสหลักมักเพิกเฉย

หรือไม่ให้ความสำคัญต่อความทุกข์ของพวกเขา, เป็นการค้ำยันทำให้ชีวิตที่มีศีลธรรมเป็นไปได้. และ, บางทีอาจมากกว่าผลงานทางวิชาการของเขา คือ

เขาเป็นตัวอย่างของปัญญาชนและศีลธรรมอิสระ ที่ค้ำจุนทุกคนที่รั้นฝ่าสวนกระแสฝูงชน

เพื่อพูดความจริง.

“I cannot tell you how

many people, myself included, and this is not hyperbole, whose lives were

changed by him,” said Finkelstein, who has been driven out of several

university posts for his intellectual courage and independence. “Were it not

for Chomsky I would have long ago succumbed. I was beaten and battered in my professional

life. It was only the knowledge that one of the greatest minds in human history

has faith in me that compensates for this constant, relentless and vicious

battering. There are many people who are considered nonentities, the so-called

little people of this world, who suddenly get an e-mail from Noam Chomsky. It

breathes new life into you. Chomsky has stirred many, many people to realize a

level of their potential that would forever be lost.”

“ผมบอกคุณไม่ได้ว่า

มีคนมากแค่ไหน, รวมทั้งตัวผมเองด้วย, นี่ไม่ได้พูดเกินความจริง,

ที่ต้องเปลี่ยนแนวทางชีวิตเพราะเขา” ฟินเกลสไตน์กล่าว, เขาถูกขับออกจากตำแหน่งในหลายมหาวิทยาลัย

เพราะความกล้าหาญและอิสระทางปัญญา. “หากไม่ใช่เพราะชอมสกี้

ผมคงแพ้ยับเยินไปแล้ว. ผมถูกทุบตีเตะต่อยในอาชีพของผม. เพียงความรู้ที่ว่า คนๆ หนึ่งที่มีจิตใจยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุดในประวัติศาสตร์มนุษย์

มีความศรัทธาต่อผม ได้ช่วยชดเชยการถูกรังแกที่ไม่หยุดยั้งนั้น. ยังมีคนอีกมากที่ถูกตราว่า เป็นพวกไม่มีตัวตน,

ที่เรียกว่า คนตัวเล็กตัวน้อยของโลก, ในบัดดล ก็ได้รับอีเมลจาก นอม ชอมสกี้. นั่นเป็นการให้ลมหายใจใหม่แก่ชีวิตผม. ชอมสกี้ได้กระตุ้นให้หลายต่อหลายคน

ให้ตระหนักถึงระดับศักยภาพของเขา ที่ไม่งั้นก็จะสาปสูญชั่วนิรันดร์”.

© TruthDig